by Gini Graham-Scott | Jun 8, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Books, Marketing Tips - Films

Today, if you are seeking to pitch a book, script, or yourself to get published by a mainstream publisher, sell film rights for a book or a script, find an agent or manager, or get paid speaking engagements, it’s all about platform.

That means you need a solid track record in your field, expert credentials in what you write or speak about, a high-profile in the print and broadcast media, and a large social media following. In short, in today’s media and celebrity driven world, you need to do something to stand out. That typically means doing your own publicity and social media campaign to create a brand for yourself, whether you write books, scripts, or films, or conduct workshops on some topics.

This platform has become especially important to sell both nonfiction and fiction books to mainstream publishers, though these guidelines are equally applicable to any field where you are creating creative content. At one time, publishers would build campaigns around new authors to establish them in the media firmament. But now, with rare exceptions, that is no more. New authors have to bring to the table their own marketing and publicity campaign, and already have key elements of this campaign in place, such as 50,000 or more Twitter followers.

Occasionally, once unknown people break through the media clutter, when they are discovered through a human interest story that goes viral. Then, agents come knocking on their doors to represent them, and they get offers of publishing and films deals based on their life story, as well as requests to speak at big events. They may even get merchandising offers to feature them in a line of products based on their story. But mostly, the already famous, such as Hillary Clinton, Bill Clinton, Angela Jolie, Kim Kardashian, and other household names are the ones who get the deals.

Thus, to stand out yourself, you need to create a powerful platform to get a deal. As Carole Jelen and Michael McAllister write in their book: Build Your Author Platform: The New Rules: A Literary Agent’s Guide to Growing Your Audience in 14 Steps, “An author’s platform is the most powerful key to success in today’s saturated market, and increasingly publishers are demanding that new authors come to them with an existing audience of interested followers. Authors who are self-publishing have an even bigger need to build an engaged audience.” The same might be said for authors who want to sell scripts or film rights to a book, or for speakers seeking to get booked on the paying speaker circuit.

So what are these elements that make a platform today? They include the following:

1) a personal website which features you and your books or other creative endeavors; and today your website should be optimized to be viewed on mobile platforms;

2) a blog to build a community with your readers;

3) a Twitter account and following, which you should build up to the many thousands; preferably 50,000 or more;

4) a presence on Facebook with both a personal page for your personal brand and a page for your book, film, or speaking topics;

5) an author’s profile and following on LinkedIn;

6) speaking engagements, featuring your live personal appearances at organizations and events;

7) articles published through various publications and websites, including on article aggregator sites, such as Huffington Post;

8) radio podcasts and guest appearances;

9) book or script trailers and video blogs on YouTube;

10) a website for each of your books or creative endeavors;

11) an author page on Amazon;

12) book reviews of your books;

13) a celebration launch of your book, film, workshop, or other creative projects.

You should also send out or post regular press releases, such as through one of the PR services, like PRBuzz, PRWeb, PRWire, BusinessWire, Cision, or ExpertClick. Additionally, make yourself available to promote what you have written or created, and let the media know you are an expert in certain areas, so you get called to comment on recent developments in your field. For example, when I wrote a series of books about crime, I was frequently asked to comment on the latest criminal cases in the news; when I wrote several books about relationships in the workplace, I was often called to comment on work issues, such as complaints about bad bosses and office shootings.

If you write a book proposal, feature what you have accomplished in the areas related to your topic and indicate where you already have a following. For example, in my proposals, I note that I am the organizer and assistant organizer of 10 Meetup Groups in L.A. and San Francisco dealing with writing and films that have nearly 10,000 members. Note any business groups you belong to such as a local Chamber of Commerce. Indicate if you have a speaker’s video and provide a link. As relevant, point up your academic credentials, such as if you are writing or speaking about mental illness and have a PhD in psychology or have worked with hundreds of clients. Highlight the most influential media attention you have already gotten from newspapers, magazines, the Internet media, and radio and TV guest appearances and interviews. Also, consider self-publishing a book in your field to help you gain additional credibility and speaker’s engagements.

In short, think of yourself as a celebrity in the making as you create your author’s brand and platform. If you need assistance with any phase of this process, from writing your book or script to getting published, produced, or promoting yourself, Changemakers Publishing and Writing (www.changemakerspublishingandwriting.com) and Publishers Agents and Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com) can help.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on writing and publishing books: FIND PUBLISHERS AND AGENTS AND GET PUBLISHED and SELL YOUR BOOK, SCRIPT, OR COLUMN. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 scripts for features, and one feature SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE, which she wrote and executive produced, is scheduled for release in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which have meetings to discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.

by Gini Graham-Scott | Jun 2, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Books, Marketing Tips - Films

One issue that frequently comes up in workshops or online forums is whether you need a copyright for your film or book. Occasionally people ask if they can use what is sometimes called the “poor man’s copyright,” where you send yourself your material in a sealed envelope, so you can later prove that you wrote it when you did.

First, the “poor man’s copyright” is perfectly useless. It is a myth that makes the rounds from time to time, usually because someone has just heard about it from someone else and wants to find out if it is true. Well, it isn’t. At best it might establish a date of mailing. But there are so many loopholes in that mailing to make a proof of anything problematic. A big problem is that one can easily steam open an envelope or mail an unsealed or empty envelope to oneself, and then put the document in the envelope and seal it up after the unsealed or empty envelope comes back in the mail.

Another misconception is that you need to formally register a copyright with the U.S. Copyright Office in order to have a copyright. You actually have a copyright from the date of creation once you write your book, script, article, proposal, or anything else. You are similarly covered by a copyright when you draw something, compose music, record a song, or other creative work and record it in written, visual, or aural form, though you can’t copyright an idea or title. A title might be covered by trademark, if you are using it or intend to use it; but that’s a more complex subject, since you can choose from several dozen categories in which to register a trademark, and you can run into complications when you use a trademark in one geographic area and another person creates the same or similar mark in a different geographic area, depending on what categories you each are claiming. But for all practical purposes, if you write a book, book proposal, script or other written materials, you are dealing with copyright law and the Copyright Office in Washington, D.C.

So essentially the question you are really asking is: “Should you ‘register’ a copyright?” with the U.S. copyright office. If you are writing a script, there is also a possibility of registering it with the WGA (Writers Guild of America), either in Los Angeles or New York, though most register it in Los Angeles, and some producers and agents/managers may ask you to do this. However, that’s not the same as registering a copyright with the government; a WGA registration is more like just putting it on a list that establishes your date of conception, and then you have to renew the WGA registration every 5 years if you register it in L.A., every 10 years if you register in New York.

By contrast, registering a work with the Copyright Office gives you a registered copyright as of the day of registration. The most efficient and economical way to do this is to register online, which is currently only $35 for an individual copyright, meaning just one item is being copyrighted by one author. If there are more authors or this is a combined registration of different properties, it is $55 to register online. It costs more to go the old fashioned postal mail route — $85 — and it will take 2 months or more to get your registration. Ideally, go through the online system, where you are walked through a step by step process to answer each question about the name of the author, date of registration, and other data. Next, you are directed to pay and upload a file with your material (although you can mail it in instead). Then, your answers are entered into the copyright form which is sent to you in a few months.

The costs can mount up if you have multiple items you want to register, so you might consider whether a copyright is really necessary. Take into consideration the fact that a copyright gives you the right to pursue your rights online or in court, but you have to take actions to enforce your copyright, which can be time consuming and expensive. For example, the most cost effective way of using a registered copyright is to prevent someone else using your material online, such as by sending this information to the offending website owner or to a web hosting company which is hosting a website with your copyrighted material. You just send a take-down notice with evidence of your copyright, and normally the hosting company will take it down if the website owner doesn’t.

However, it is very expensive to take any legal action in court to enforce a copyright, so a registration won’t be of much use if you are seeking compensation from someone who has improperly posted your material online and doesn’t have any money. But if you wait, maybe they will have money or they may arrange for someone else with money to use your material – at which time, you can inform them that you own the copyright and you aren’t giving your permission without a just compensation, whereupon you can negotiate the terms with them if they willing to do anything. Otherwise, you have the basis for taking them to court and claiming statutory damages, which may lead them to drop your material or seek an agreement from you.

In general, given the expense and limitations of a copyright, it is not necessary to register the copyright for a proposal or manuscript. The situation is different if you self-publish a book or if a traditional publisher publishes it and, as is usual, assigns the copyright to you. In this case, the publisher will generally file for the copyright in your name. If not, it is a good idea to file for copyright yourself, especially if you feel the book has a good commercial value for a general audience, since there is more risk of someone using your material or even filing a registration on a copy of your work.

Otherwise, if your work is unpublished, it may not be worth the time and expense, since publishers and agents are unlikely to use your material without you, since publishers generally want you as the author to be front and center to promote your book. And normally there isn’t the kind of money in a published book as there is in a produced film or recorded song. So with a book, unless it just makes you uncomfortable to not register a copyright, I feel it isn’t necessary – especially if you have written many books, because of the high cost involved. Even if you self-publish a book, it may not be necessary to register a copyright, especially if you have published multiple books, so the registration costs are high, since most self-published books average about 150 copies in sales.

So if someone pirates your book, it probably doesn’t matter whether your book’s copyright is registered or not, since it is unlikely you can do much more than send a take-down notice to the multiple sites offering free copies of your book and hope they take it down. If they don’t, it’s not normally cost-effective to try to pursue matters any further.

Likewise, if you write articles it is not necessary to copyright each one, especially when you are making the articles available for free. Just use them for promotional value, though if you combine the articles together into a book and self-publish it, you might get the copyright then.

By contrast, if you complete a script, treatment, or TV series or show proposal, it is a good idea to register a copyright, whether or not you get a WGA listing. Many producers for their own protection will want you to have a registered copyright, and often any NDA document they ask you to sign will have some language about your having only the protection in what you have copyrighted and not in any similar ideas they might have developed in house or obtained from another writer or other party.

Another reason for registering a copyright in the film world is because it is so competitive, and sometimes, if a script reader sees the potential in your idea, it could be shared with others, though it might undergo some further changes in the script. Then you could be out of the loop, although a registered copyright will make it more likely for you to be involved in the project going forward. Or it could lead to a payoff to get your copyrighted material signed over from you.

In sum, in the case of books and articles, it is generally not necessary to get a copyright unless you have high hopes for a large commercial sale or are willing to pursue take-down notices or a court case against someone who copies and sells your book and has the money to collect if you win. But if you write a script, TV show proposal, or treatment, get your material registered, since you will often need it to even get your script considered by producers, agents, managers, or others in the film industry.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on writing and publishing books: FIND PUBLISHERS AND AGENTS AND GET PUBLISHED and SELL YOUR BOOK, SCRIPT, OR COLUMN. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 scripts for features, and has one feature film SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE, which she wrote and executive produced, scheduled for release in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which have meetings to discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.

by Gini Graham-Scott | May 12, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Books, Marketing Tips - Films

Sometimes professional writers are offered the opportunity to work as a co-writer. Should you do it, and if so, what the best way to protect yourself should problems develop?

Co-writing can be an ideal arrangement, when you have long been friends or business associates and you both share a passion for the project. Then, you can bounce your creativity off each other and create a great project together.

But what happens when you are approached by someone who thinks they have a great idea, and now they need a writer to make that happen? In many scenarios, this can turn into a paid project where the writer works as a ghostwriter and is paid on a work-for-hire basis by a client, or this can turn into a co-writing agreement when both parties work well together.

I believe starting with a work-for-hire agreement is an ideal arrangement when you are approached by someone you don’t know, because you don’t know how well you will work together or if you will share a similar vision for the book or a film project as it develops. This way, if the person with the project has the budget, he or she can maintain control of the project, while you write what the person wants. Then, if the relationship works out and you both want this, you can turn the book or film into a shared royalty agreement. One common scenario is for the writer to finish the project at a lower fee, such as less 25-35%, in return for a percentage of the royalty (commonly 50-50) after anything paid up front is deducted.

Often the situation of a shared royalty arrangement from the start comes up when the person with the idea, notes, or a rough draft has a limited budget. This shared agreement can work well, if you soon come to share the writer’s vision of the final project and you feel comfortable sharing in the project. Also, it can work well if the project is in your own field of expertise, and you feel the project has a good likelihood of getting sold, so you aren’t giving up the regular income you depend on in return for something that’s a risky bet.

However, there are a number of cautions to watch out for in co-author arrangements with someone you don’t know well, such as when you respond to an ad for a writer to be a collaborator or co-writer. One problem is that you may start off agreeing that this is a shared project, but then the original author becomes controlling and you start to feel like a hired hand, as happened to one writer who was enticed into doing some chapters for a book by a psychologist. The psychologist claimed she wanted someone to be a true collaborator and share the authorship and royalties. But then the psychologist turned into a tyrant, who was very critical of what the writer wrote, because she wanted everything expressed a certain way. Eventually, the writer was able to escape the nightmare with a signed work-for-hire agreement and got paid in full for what he had discounted to be a collaborator.

Another problem in a co-writer project occurs when the original author has less and less time to contribute to the project or loses interest, because of other commitments. So there isn’t enough information to complete and sell the project, and the writer is stuck with getting less or nothing, because of agreeing to a collaboration. For example, one writer faced this situation after writing situation when the client writing his memoir suddenly decided that he shouldn’t do this book now, because his psychiatrist thought it wasn’t a good idea. Besides, now if he did pursue the book, he wanted full control of both the book and the possible film based on it. Fortunately in this case, the writer was able to turn the collaboration into a work-for-hire situation for the work already done and get paid accordingly. But in many cases, a project simply dies at this point, and the writer doesn’t get paid.

The other big problem with a collaboration is that when the project is completed, it may not sell or may only bring in a very small advance, which is less than the author would get paid for writing the book, proposal, or script as a ghostwriter. Then, if there is a very low or no advance, any future work on the project has to be written largely or solely on spec.

Thus, given all these potential problems, my usual approach is to start off as a ghostwriter for at least the beginning stages of the project. Then, if the project is in a field I normally write about and we both feel a co-writing arrangement is desirable, we sign a co-writing agreement, and I reduce the total costs on the project by 25% in return for sharing in the proceeds should it sell. Thereafter, the original author is paid back in full for anything paid to me, before we share in the royalties 50-50. Such a deduction before sharing royalties is a typical arrangement, and I have found this approach works best for me.

What’s best for you? I suggest treating each co-writing arrangement on a case by case basis, taking into consideration the topic, how much you like both the project and the author, the potential for selling the book or film, and how much a sale is likely to bring. Then, compare that to what you would make as a ghostwriter, since normally the most you will earn on most books and films is what you are paid as an advance. Additionally, consider your own income needs and whether you can afford to take a chance on getting less up-front as a co-writer, and whether starting this project as a co-writer is the only option, because that’s all the original writer can afford.

* * * * * * *

GINI GRAHAM SCOTT, Ph.D., is a nationally known writer, consultant, speaker, and seminar/workshop leader, who has published over 50 books on diverse subjects, including business and work relationships, professional and personal development, and social trends. She also writes books, proposals, scripts, articles, blogs, website copy, press releases, and marketing materials for clients as the founder and director of Changemakers Publishing and Writing and as a writer and consultant for The Publishing Connection (www.thepublishingconnection.com). She has been a featured expert guest on hundreds of TV and radio programs, including Good Morning America, Oprah, and CNN, talking about the topics in her books.

by Gini Graham-Scott | Feb 19, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Books, Marketing Tips - Films

Co-writing and ghost writing arrangements for both books and scripts can be great when you and your co-writer or lead writer have a shared vision for the project and you bring to it complementary skills. Besides writing my own books and scripts, I have worked with several dozen clients on co-written projects.

A first step is understanding what the person seeking a co-writer or ghost writer wants and clarifying what you will do. In reaching this understanding, determine this person’s goals – is this to be a proposal for a books and some sample chapters, a complete book, a treatment for a film, a complete script, or whatever else the person wants written.

Also, work out the financial arrangements, including whether the client will be paying for this as a work for hire or as a co-writing arrangement, or if this is starting out as a work for hire, which will be transformed into a co-writing project if you mutually agree. Then, too, determine how the client will pay – based on a per word or per page basis or an hourly rate – and if it is per page, clarify approximately how many words per page this will be, based on the type font you are using.

Additionally, determine up front how the client will pay. Some like a contract, where you get a certain percentage down (ie: 20-33%), another percentage after you complete a certain amount of the manuscript (ie: another 20-33% after you complete ¼ to ½ of the manuscript), still more at the next percentage point, and at the end. Another common alternative is to use a pay as you go model, where the person pays you a set amount via PayPal or check for each segment of the project before you do it or where you charge that person’s card a certain amount before or after you do each section.

With more established companies, a common arrangement, if you don’t have a contract for money up front for each section of the project, is for you to bill the company, after which they pay you within 10 to 30 days. And usually they do. While such a billing arrangement may be fine with larger established companies or with a client with whom you have an ongoing long-term relationship, I don’t recommend this for new individual clients, especially if you haven’t met them personally or they are in another state or country. The big problem is that you can do the work and they don’t pay you. Then, you have little or no way to collect, because the client is out of state and this is too small amount to pursue through legal means, plus then you still have to collect if you win.

Sometimes clients may argue that they don’t want to pay anything up front because they aren’t sure that you will complete the work or that they will be satisfied. One good response to that is to assure them that they are protected if they pay you by credit card, because they can ask for and obtain a refund from their credit card company for non-completion of the project, whereas you have no such protection if they don’t pay you. As for their comment that their payment hinges on whether they will be satisfied, this could be a red flag that you are dealing with a difficult person who is hard to satisfy, and they could refuse to pay you for that reason, too.

To deal with that issue, I generally respond that I don’t work on spec and that I can limit what I do to a small number of pages (say 5-10 pages). Then, they can provide me with their comments so I can revise what I have written if necessary, and if satisfied, they can give me the go ahead to do more. But otherwise, I get paid for what I do, and I will do everything I can to make sure they like what I am doing, before I do more.

Another arrangement I will enter into with some clients is an initial co-writing agreement if the project is in my field and I think I will like working with this person, if the person insists on such an arrangement to do the project. Then, I will deduct 25% from my usual charges in return for a credit and splitting any royalties or fees for selling the project, after deducting whatever the person paid me upfront, though I give the client the option of turning the project into a work-for-hire before pitching it for sale by paying me the additional 25%. But ideally, I prefer to start as a work-for-hire arrangement with the option of turning this into a co-write down the road. This way, it is very clear that client is in control from the get-go, and as the project goes along, we can mutually determine if a co-writer arrangement would be mutually beneficial. Otherwise, the client is in the driver’s seat, steering the project, so he or she knows the destination, and my role is to help the client get there. The advantage of this arrangement, I have found, is that there are no problems of co-writers discovering they have different shared visions of the project as they go along, since it starts with the client’s vision and can always turn into a co-write if this vision is shared.

* * * * * * *

GINI GRAHAM SCOTT, Ph.D., is a nationally known writer, consultant, speaker, and seminar/workshop leader, who has published over 50 books on diverse subjects, including business and work relationships, professional and personal development, and social trends. She also writes books, proposals, scripts, articles, blogs, website copy, press releases, and marketing materials for clients as the founder and director of Changemakers Publishing and Writing and as a writer and consultant for The Publishing Connection (www.thepublishingconnection.com). She has been a featured expert guest on hundreds of TV and radio programs, including Good Morning America, Oprah, and CNN, talking about the topics in her books.

by Gini Graham-Scott | Jan 13, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Films

In order to properly position and promote your film, you need very good, professional-looking art work for your poster and screener cover, and later this poster art can be used for your home video cover, sales on your website, catalog sheets, and other materials.

Having good art will help your film stand out, convey what it is about, and show you have a good film, since you have taken the care to make it good. Also, whether you pay to have a professional design your art or have some who’s very good with graphics on your team, good art conveys the high value placed on the film, which is important when a distributor seeks to sell it. By contrast, if you have amateurishly looking art, that will detract from your film, no matter how well-done, by making your film look like an amateur effort, since the value of the art transfers to the perception of the quality of your film. Consider this art like a book or music album cover which helps sell the book or album.

If you don’t have a top-notch graphics designer on your team and can afford it, hire a top professional. Figure the cost will be about $1000-3000. You might find some good contacts in your area through a local Chamber of Commerce directory or a business mixer. Other possibilities include business referral and networking groups, such as BNI (Business Networking International), which has chapters all over the U.S. in major cities. If you have a limited budget, to keep your costs down you might find someone through a local college or art school. Just contact the school’s placement center or ask an instructor teaching a class on graphics design to tell the class about your job opportunity. You might also have some success posting a notice for a designer on Craigslist or going to one of the freelance websites that feature work by freelancers who work at a lower rate, largely because they are located outside the U.S., such as www.guru.com or www.elance.com. Years ago I hired someone through Elance from Australia, and I hired some students from San Francisco State for some art projects.

To choose someone with the kind of style you like, look at the prospective designer’s portfolio – either through a personal meeting or online. To help determine the look and feel of your film, look at some covers and posters for other successful films in your genre to see the approach used. For instance, if it’s a horror film, you will probably want dark, somber tones that convey mystery and danger. You may want to incorporate images of ghosts, injuries, weapons, or other sorts of destruction and fear are conveyed in your film. As an example, if your film takes place in a haunted house and nearby cemetery, where many characters are attacked or die, incorporate images of the house and gravestones, along with people falling down and perhaps bleeding onto the cellar steps or graves. Alternatively, if your film is a romantic comedy, use light colorful graphics to convey that this is a happy, humorous film, and perhaps feature the romantic couple having fun together. For more specific guidelines, go to a store that rents or sells videos or look online where these videos are on sale to see the posters or covers. While the big video stores are gone, many videos are available at your local supermarket, drug stores, or other venues.

Once you have chosen your graphics artist or have narrowed down your search to a few artists, start with some sketches to illustrate the concept or concepts you are considering for the final art. It can also be helpful to get some feedback or suggestions from others on how they see the film’s poster and cover. In some cases, you might use a preliminary poster that you previously used in pitching the film to interest cast and crew to participate, and that can be a starting point for your final poster and cover.

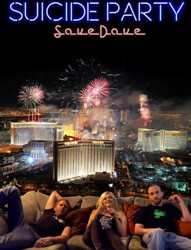

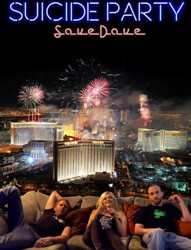

For instance, in the case of SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE, the director was also a skilled graphics designer, who had previously created posters and screen covers for over a half-dozen previously distributed films. So he already knew how to create a powerful image to present the film. Initially, he created a light-hearted but quickly drawn poster to show the film was a comedy drama, though a little dark in light of the words “suicide party” in the title. But this initial design was not intended to be the final poster or cover art.

Later, after the trailer for the film was completed and he was working on the final art, he wanted to have a strong image conveying the excitement of Las Vegas in the video, since the city played a central role in the film. Also, he wanted to include a photo of the three main characters enjoying themselves there, as the primary lead Dave sought to raise money for the party, while his best friend Steve, filmed the action for a crowdfunding campaign being run by his wacky friend Gidget. But he was open to other suggestions.

Though I proposed creating a composite image of the three main characters in the desert looking at Las Vegas as a symbol of hope in contrast to the desolation of the desert, where Dave is contemplating his future and plans for the fundraising campaign, ultimately that concept wouldn’t work, since during filming, there were no shots of the three lead characters together. So ultimately the image became a mash-up of the three lounging on a couch, with the fireworks lighting up the night skies of Vegas behind them.

Besides the title for the film, include the names of the lead actors on the poster art, and you might additionally include a short catchy line, sometimes called a “tag line” or “slogan”, which sums up what the film is about, if it adds to the image. Alternatively, whether you use this tag line on the poster or not, you can readily use it on the back cover of the screener box or in your promotional copy, such as my suggested line for SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE: “If all seems lost, would a suicide party help?”

Before you finalize the art and any slogan or tag line, it’s a good idea to test it out not only with some cast and crew members, but with others who are following the progress of the film. For instance, the SUICIDE PARTY director posted two possibilities of a final cover — one with the fireworks over Vegas, the other with Vegas coming alive at night — on Facebook and asked people to share their comments and preferences. The result? The fireworks over Vegas image was the clear winner, so that’s the image he decided to use, though as of this writing, the tag line and whether to use it on the cover is still being tested.

Once you have this final art selected, use it for the poster, screener box cover, postcards, press kit cover, website, and anything else with graphics for the film, since this image will become like a brand for your film. Having great art helps to not only show it’s a great film, but you reinforce the film’s image in the mind of potential distributors, buyers, the press, and the public, and show it’s an exciting, professionally done film, thereby furthering the odds that people will want to promote, sell, and see it.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on films: HOW TO WRITE, PRODUCE, AND DIRECT A LOW-BUDGET SHORT FILM and FINDING FUNDS FOR YOUR FILM OR TV PROJECT. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 feature scripts, and has one feature she wrote and executive produced to be released in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.

by Gus | Jan 11, 2015 | Marketing Tips, Marketing Tips - Films

There are two approaches for assessing distributors. One is do an assessment before you contact distributors to decide who to contact in the first place. The other is do this review after you have contacted many distributors, such as through a personalized email query blast where you describe your project and ideally include a link to a trailer, after which some distributors express interest in learning more.

Unless you have personal referrals or have met distributors at an event, such as a conference or workshop, I prefer the email query approach as more efficient, since you use the initial query to target distributors who might be interested. Then, if you get a high level of interest, you can assess the distributors to decide those to follow through with by sending them a screener and promotional materials. You can readily add additional distributors to his initial list. Or simply send all the distributors who have expressed interest the screener and promotional material, and do your assessment afterwards of the remaining interested distributors .

Whatever your initial approach, doing the assessment in advance to decide who to contact or doing it afterwards to decide which still-interested distributors to consider making a deal with, here are some factors to consider in making your assessment and selecting a distributor for all or selected channels and territories.

One approach, especially if you think your film is good enough to go theatrical and you are willing to make the necessary investment for marketing, is to look at the success of these distributors with previous films, as well as whether they distribute your type of film. For example, some distributors specialize in action/adventure films, others in sci-fi, documentaries, comedies, or drama, and some cover most types of films. You want to target those that best fit your film in making initial queries or discussing your film’s prospects after distributors have expressed interest.

One good source for assessing distributors is looking at their profile on IMDB (the International Movie Database) to see how many films they have distributed, when they did so, what type of films these were, and how well these films did. After you review their profile and get a list of their films, you can check the listing for each film to see its description, the cast, and the film’s current rating. You need a professional IMDB subscription to do this, which is around $20 a month, so sign up if you don’t already get this.

That’s the kind of assessment I did in arranging distribution for SUICIDE PARTY: SAVE DAVE. After I sent out an email query and about 20 distributors expressed interest and wanted to see the screener, I forwarded their letters to my director, who had previously filmed and distributed over a dozen films, so he could review and rate the distributors. He then came back with his report, indicating which distributors had the best track record after eliminating those who had only distributed a few films, and in one case, only a single film several years earlier. You can’t always get this kind of information from the directories of distributors, so you need to do this checking.

If you have a choice of multiple distributors, this approach can help you find the distributor who is likely to do the most for your film, due to his or her past performance. However, you still need to evaluate the contract and deal you are being offered to determine if that is still the best distributor for your film.

For example, if a good distributor wants a 50-50 deal, while a distributor with only a limited track record wants 35%, it may be better to give up a greater percentage, since, as my director put it, “Thirty-five percent of nothing is nothing.” On the other hand, many distributor deals are for 35%, especially if a distributor feels you have a strong film, and some new distributors may turn out to be very eager and hungry, so they will be very proactive in pushing your film.

Another consideration is whether a distributor expects any money from you for P&A (promotion and advertising) or E&O (errors and omissions) insurance.

Another approach if you want to go theatrical is to look at which distributors are most active in distributing films playing at theaters, along with the genres, grosses, and the number of theaters in which these films have played. This way you can rank the distributors for your type of film based on their box office performance, taking into consideration both the number of films these distributors have represented and the films with the highest grosses.

While you can get the weekend box office grosses for nearly 100 films a week for many previous months, I would suggest just using the Weekend Domestic Chart for the past month to make your analysis more manageable. While the big budget grosses as might be expected are from big studio distributors and their affiliates, some independent distributors have respectable showings of $50,000 or more at the box office, and some have films which have gotten $15,000 or more. Take into consideration the total grosses and how many days the film has been out, so you can more realistically assess how well a film has done during its box office run.

For example, when I did this for the four week period from November 21-December 12, 2014, I found the following distributors for the most films in all genres, although when you do this, limit it your genres. All of these genres include the following:

– Drama

– Thriller/suspense

– Comedy

– Adventure

– Black Comedy

– Horror

– Western

– Action

– Documentary

– Romantic comedy

– Multiple Genres

Based on these listings for this period, these distributors had the highest grossing films, and most of these distributors had multiple films in different genres. I have listed the distributors based on their total grosses for at least one film. In doing your analysis, keep track of the number of films from a distributor, the genre, and the individual grosses.

Gross of $2 Million or More

– Lionsgate

– 20th Century Fox

– Paramount Pictures

– Walt Disney

– Universal

– Focus Features

– Fox Searchlight

– Weinstein Company

– Open Road

– Sony Pictures Classics

– Roadside Attractions

– Relativity

– Sony Pictures

– Radius-TWC

– Magnolia Pictures

– Samuel Goldwyn Films

– Lorimar Motion Pictures

– Cohen Media Group

Gross of $100,000-$2 Million

– IFC Midnight

– China Lion Film Distribution

– MacGillivray Freedman Films

– Zeitgeist

– GKIDS

– Counterpoint Films & Self-Realization Fellowship

– Area 23a

– Eros Entertainment

Gross of $25,000-100,000

– International Film Circuit

– First Run Features

– Music Box Films

– Dada Films

– Aborama Films

– Strand

– Drafthouse Films

– Oscilliscope Pictures

– Rialto Pictures

Since this list comes from only one month of box office listings, other distributors may show up if these listings were drawn from other months, several months, or a year.

And what if you don’t have the luxury of choosing among many distributors, since you only have very few offers, even only one? Then, make the assessment based on whether you want to select this distributor at all or either wait for another distributor or self-distribute your film, at least for a awhile.

In sum, if you have one or more distributors to choose from, in making an assessment, factor in the distributor’s track record along with other considerations to decide which one or ones to go with for your film. To make the best choice, the art of picking the right distributor or distributors (including the right foreign sales agents or agents) can be an involved, time-consuming process – from finding interested distributors to finding the right one or ones to work with. But it’s important to make this assessment carefully; it’s like entering into a short-term marriage, and if it works, you want to renew it; if not, you move on and look for other possibilities. Just carefully assess your options, in light of what’s realistic for your film, so you start out with a good marriage for your film.

*************

Gini Graham Scott, PhD, is the author of over 50 books with major publishers, including two on films: HOW TO WRITE, PRODUCE, AND DIRECT A LOW-BUDGET SHORT FILM and FINDING FUNDS FOR YOUR FILM OR TV PROJECT. She has written and produced over 50 short films, has written 15 feature scripts, and has one feature she wrote and executive produced to be released in February 2015. She also writes scripts for clients, is Creative Director for Publishers Agents & Films (www.publishersagentsandfilms.com), and has several book and film industry Meetup groups which discuss members’ books and films and help them get published or produced.